It turns out that the two Border Patrol officers accused of killing Alex Pretti are themselves of Hispanic background. According to ProPublica, their names are Jesus Ochoa, who is 43, and Raymundo Gutierrez, who is 35.

For a lot of people who are honestly trying to understand what’s happening, this fact is confusing. They ask a reasonable question: how can men with Hispanic roots work for a force that many people believe exists to intimidate, harm, or terrorize Hispanic communities?

At the same time, this detail is being used very differently by people who argue in bad faith. Critics of Donald Trump say that agencies like ICE and CBP are being used to target Latinos as part of a broader goal of pushing the country toward a white-dominated future. His supporters, on the other hand, point to officers like Ochoa and Gutierrez and say, “See? This has nothing to do with race. Latinos support this too.” That back-and-forth only adds to the confusion.

Racism, unfortunately, is very real. But the idea of race itself is not a biological fact; it’s a social invention. When people argue endlessly about something that isn’t real in a literal sense, it creates confusion, and confusion is exactly what bad actors thrive on. So it helps to be clear about what people really mean when they talk about “white.” They are usually not talking about skin color. They are talking about power.

In this context, “white” means a system of power that puts wealthy white men at the top. They get the most protection from the law and the greatest rewards from the economy.

As you move down this pyramid, everyone else receives less protection and fewer benefits. At the very bottom are Black and brown people, who are often left with little legal protection and almost no share in economic success. This system is unequal and deeply unjust, but it has shaped American history for generations.

Some Hispanic people, sadly, want a place within that system. No matter how long their families have lived in the United States, they want access to what whiteness represents: safety, status, and power. Instead of challenging oppression, they try to align themselves with the oppressors, hoping to be accepted as equals. For them, this becomes a distorted version of the American Dream.

But acceptance into this system is never automatic. History is full of examples of immigrants and nonwhite groups who gained positions of authority and then used those roles to prove themselves to white society.

They tried to show they were not only “good immigrants,” but deserving of the rewards that come with whiteness. Loyalty had to be demonstrated, often by enforcing the system against people who looked like them.

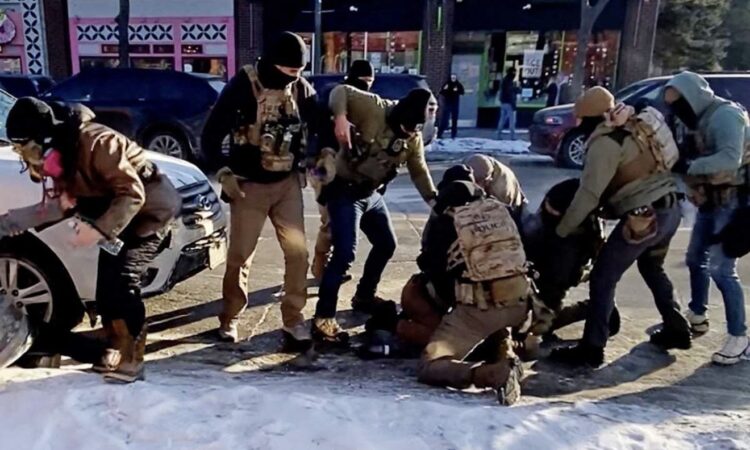

Seen through that lens, it is not ironic that Ochoa and Gutierrez worked for Trump-era border enforcement. It fits a long historical pattern. It’s similar to how some Irish immigrants in 19th-century New York became police officers and brutalized other Irish people to show that they had left their old identity behind and fully embraced the dominant white order.

In Alex Pretti’s case, there is another layer. According to the harsh logic of white power, Pretti was disloyal. He was an ICU nurse who chose to stand up for people harmed by an unfair system. By doing that, he rejected the privileges that came with his position and background.

In his own mind, he was standing up for what he believed America should be. But under the rules of white power, patriotism is not about loyalty to shared values or ideals. It is about loyalty to race.

That mindset was made brutally clear by white supremacist Nick Fuentes, who mocked Pretti after his death and dismissed him as a “race traitor.” Fuentes himself has Hispanic roots. His father is a biracial Mexican, and he speaks fluent Spanish. Yet he works relentlessly to prove that he belongs within whiteness, because for him, white supremacy is more important than heritage, empathy, or even self-respect.

From that same twisted perspective, killing or punishing someone like Pretti becomes a way to prove loyalty. What better way, in their eyes, to show devotion to the system than by violently punishing a white man who turned against it? In this logic, Pretti was deemed unworthy, while the officers who killed him were seen as proving their worth.

The deeper irony is that this chase for acceptance into whiteness sends a harsh message to other Hispanic people. No matter how hard they work, how obedient they are, or how much success they achieve, they will never be “white enough” for those who are fully invested in maintaining white power. The door is always conditional, and it can slam shut at any moment.

Recent polls suggest that whatever gains Trump made with Hispanic voters in the 2024 election have largely disappeared since ICE and CBP actions intensified. Back then, Trump said only violent criminals would be targeted. He still says that now, just with slightly different words. But far fewer Hispanic people believe him anymore.

Many people have come to understand that the word “illegal” is not really about immigration status. It is about who is seen as belonging. If you are not white, you are treated as “illegal.” And sometimes, even being white is not enough. The deaths of people like Renee Good and Alex Pretti show that stepping outside the expected racial loyalty can mark someone as a traitor, someone who deserves punishment without due process.

When JD Vance was asked whether he would apologize to Pretti’s family after the investigation into his death, he replied, “For what?” That response captured just how little value the system places on lives lost in its name.

Perhaps the biggest irony of all is what this obsession with whiteness is doing to white people themselves, especially those who see themselves as decent, respectable, and above political extremism. It is forcing them to confront their own race, something many have long avoided thinking about. And it is creating a future where they may have to choose between holding onto the privileges of whiteness and standing by the values fairness, dignity, equality that once allowed them to see themselves as good people.

Their social status and their moral values are starting to pull in opposite directions.

No one really knows how that conflict will end.